Zika and Blood Transfusions: The Current Landscape

|

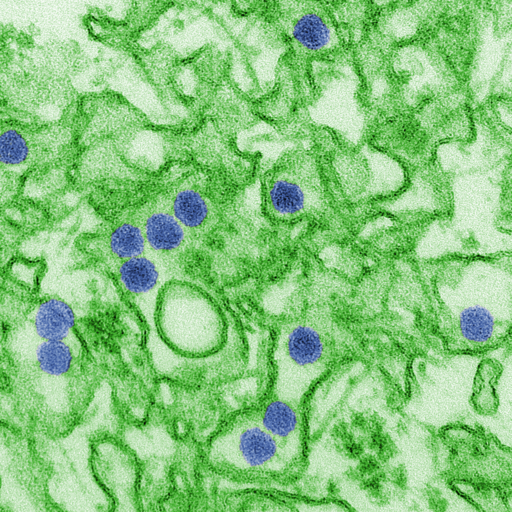

| Scanning Electron Microscope image of Zika |

Zika virus, initially identified in the Zika forest of Uganda in 1947, emerged as a significant global health concern during the outbreak that began in Brazil in 2015. Transmitted primarily through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito, Zika garnered international attention due to its association with microcephaly in newborns and other severe birth defects. Additionally, concerns were raised about the potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusions, creating an urgency in the blood banking community to implement safety measures.

Zika Transmission through Blood Transfusions

While the majority of Zika virus cases result from mosquito bites, several instances of transmission through blood transfusions were reported during the major outbreaks. The virus can survive and remain infectious in blood products, making the transfusion of contaminated blood a possible transmission route. Furthermore, a significant number of infected individuals are asymptomatic, which makes it harder to identify and defer potentially infectious donors based solely on clinical symptoms.

Blood Screening for Zika

Given the potential risks associated with Zika virus transmission through transfusions, many countries, particularly those with reported Zika cases, initiated blood screening procedures to ensure the safety of the blood supply.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance in 2016 recommending universal testing of all donated Whole Blood and blood components for Zika virus in the states and territories with active transmission. By 2018, this guidance expanded to include universal testing across all states and territories, regardless of the presence of active Zika cases. This approach utilized nucleic acid testing (NAT) to detect the presence of the virus in donated blood.

Current Testing Guidelines

Over time, as the number of Zika cases declined and a better understanding of the virus and its transmission patterns emerged, the FDA updated its guidelines. In 2019, the FDA revised its recommendations, allowing blood centers to test pooled samples rather than individual donations. This shift was based on risk-assessment models showing a significant decrease in the prevalence of Zika virus infection among blood donors in the U.S.

Internationally, blood screening protocols vary based on the prevalence of the virus, available resources, and the assessed risk of transfusion-transmitted Zika virus. Many countries with no reported cases or those that have never experienced local transmission might not routinely screen blood donations for Zika.

Implications for Blood Safety

The introduction and continuous update of Zika screening protocols signify the nimbleness required in transfusion medicine. In the face of emerging infectious threats, the blood banking community must be prepared to quickly assess risks and implement appropriate safety measures.

Zika's emergence reinforced the importance of proactive measures, research, and international collaboration to ensure the safety of the blood supply. While the immediate crisis associated with the Zika virus has subsided, the lessons learned continue to shape policies and preparedness strategies for future threats.

The Effects of Zika Virus

While many people infected with Zika virus remain asymptomatic or experience only mild symptoms, the real concern lies in the complications linked to the virus:

Birth Defects: One of the most alarming complications associated with Zika is its ability to cause congenital disabilities when pregnant women contract the virus. Microcephaly, where a baby's head is much smaller than expected, is the most recognized of these birth defects. Infants with microcephaly often have underdeveloped brains, leading to long-term developmental challenges and sometimes even death.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS): Zika has been associated with GBS, a rare neurological disorder where a person's immune system attacks their nerves. GBS can result in muscle weakness and, in severe cases, paralysis. Though most people recover from GBS, some might experience long-term effects, and in rare cases, it can be fatal.

Other Neurological Complications: Apart from GBS, Zika has been linked to other neurological conditions such as meningoencephalitis and myelitis.